This is the story of one of the most curious books in Ireland.

‘Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922‘ by G.B. Kenna is a book very much shrouded in mystery. Written and printed in 1922, thousands of copies were printed for distribution but only eighteen ended up in circulation. The rest were apparently pulped to prevent the book reaching the shops. It is, of course, well known that the author wasn’t actually ‘G.B. Kenna’ but the name of the publisher, the ‘O’Connell Publishing Company, Dublin’ similarly appears to be fictitious. So, what was going on?

Cover of the original edition of Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922

The book began in the work of the Publicity Committee of the Provisional Government in 1922 (as the early Free State government was known). Michael Collins had sent Cork man Patrick O’Driscoll to Belfast in mid-February 1922 to gather statements on the intense violence that had been happening in the city. Northern IRA units had been sending a stream of intelligence reports to Dublin with accounts of the violence since 1920. It had always been assumed by Collins, IRA GHQ and others, that these accounts exaggerated not just the extent of the violence, but Craig and the Unionists’ role in inciting it, and the behaviour of the B Specials and others that had led Belfast Catholics to label it as a ‘pogrom’ (the use of the term ‘pogrom’ is discussed further below). Given the disputes over the Anglo-Irish Treaty he signed in December 1921, at the very least, Collins now needed the northern IRA units to not openly oppose the treaty. O’Driscoll being sent was likely part of the same trust-building exercise by pro-treaty supporters in Dublin that had included a promise of arms and ammunition to the northern IRA units if they backed the treaty. Highly regarded by Collins, O’Driscoll (later a Dáil reporter) was to explore the truth of the ‘pogrom’ claims.

The statements and information O’Driscoll collected began to be appear in Provisional Government bulletins during March 1922. Collins likely sought to use the revelations as leverage during his own negotiations with the northern Unionist leader Sir James Craig (these negotiations led to the Craig-Collins Pacts). O’Driscoll also advised Collins that the Catholic bishops and community leaders were demanding that someone publish a detailed exposé to counteract the propaganda the unionist press had been printing since 1920. This included funerals of Catholics being wrongly reported as IRA victims, attacks on Catholics being wrongly ascribed to the IRA and photographs of damaged ‘Protestant’ homes that had actually been owned by ‘Catholics’. [You can read more about a typical example, Weaver Street, here.]

Collins asked the Catholic Bishop of Down and Conor, Joseph MacRory, to release Father John Hassan, the administrator in St Mary’s, Chapel Lane in the centre of Belfast, to work on gathering suitable material for a book. Hassan had previously been the parish priest in St Joseph’s in Sailortown and was familiar with, and well known in, the districts which had seen the most violence. He had also been recording the details of events since 1920. Hassan set out to gather information to address the black propaganda issues (sometimes at the expenses of completeness in his statistics).

Fr John Hassan (courtesy of his great grand nephew, Niall Hassan)

Fr John Hassan (courtesy of his great grand nephew, Niall Hassan)

Hassan, however, told O’Driscoll that he personally didn’t feel up to the task of writing a book on the subject and it was agreed with Collins that it be entrusted to a member of the Publicity Committee, Alfred O’Rahilly, who would be supplied with the necessary information by Hassan. O’Rahilly, a noted mathematician and theologian, was the Registrar of University College Cork and had been the constitutional advisor to the treaty delegation in 1921. He had helped draft a constitution for the new Irish Free State earlier in 1922 and was very much a Catholic intellectual, having initially trained as a Jesuit. O’Driscoll said that O’Rahilly was going to write “…one of the most powerful indictments of Orangeism ever published” (see J. Anthony Gaughan’s biography of O’Rahilly).

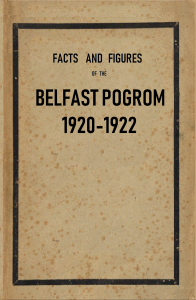

Special Branch photo of Alfred O’Rahilly who it labels as Director of SF Propaganda

Special Branch photo of Alfred O’Rahilly who it labels as Director of SF PropagandaAfter the Provisional Government’s North East Advisory Committee met on 11th April 1922 to review events, O’Rahilly met with Collins on the 20th and agreed to write the book. In early May he sent an outline to Kevin O’Higgins’ secretary (Patrick McGilligan) but O’Rahilly was then busy with university business until June. As Kieron Glennon has pointed out (in From Pogrom to Civil War), the dire reports from the north at the 11th April meeting and O’Driscoll’s eye witness accounts surely alarmed Collins and Richard Mulcahy over their capacity to retain the confidence of northern IRA units. Mulcahy had been Chief of Staff of the IRA and was now Chief of Staff of the new Free State’s ‘National Army’. They then agreed to an abortive, disorganised and ultimately futile northern offensive by the IRA in mid-May 1922. That offensive eroded most of the northern IRA’s remaining resources and capacity to no obvious purpose (other than perhaps diverting their attention from events further south).

In early June, O’Driscoll wrote to O’Rahilly to advise him that all the necessary material was now available. He also told O’Rahilly that Fr Hassan was starting to get uneasy as he hadn’t yet heard from O’Rahilly. By now, though, the outbreak of hostilities between pro- and anti-treaty supporters had taken centre stage in the south. The Provisional Government set-up a new North East Policy Committee without Collins but including the likes of Ernest Blythe, a republican with a northern Protestant background. Hassan continued to work on collecting information for the book. O’Rahilly’s public standing, though, meant that he was caught up in attempts to broker peace between pro- and anti-treaty supporters in Cork and he seems to have been unable to commit to completing his part of the work at the time. According to Gaughan it was then decided that, as an interim report, Hassan would publish the information he had gathered to date as a book. This was to be funded by Collins and O’Rahilly would follow it with his own devastating polemic in due course.

So Hassan pulled together the material he had gathered to date. He appears to have finished up at the start of August as the book contains details of sentences handed out in court in Belfast on the same date that he wrote the foreword, 1st August 1922. The foreword explicitly set out the motivation behind writing the book: “…to place before the public a brief review of the disorders that have made the name of Belfast notorious… A well-financed Press propaganda… has already succeeded in convincing vast numbers of people, especially in England, that the victims were the persecutors… What the Catholics of Belfast would desire most of all…is an impartial tribunal set up by Government to investigate the whole tragic business… considering the magnitude of these outrages…?”

But by the 1st August 1922 Michael Collins had only three weeks left to live.

The timing seems to be quite significant. On 2nd August Collins and the northern IRA units had agreed to cease offensive operations in the north and were instead to adopt a policy of passive resistance and non-recognition of the Northern Ireland government. The 3rd August issue of the Irish Bulletin from the Publicity Committee included a summary of some of the information gathered by Hassan. The next day the Freeman’s Journal called it a “…an admirable antidote to the lying propaganda which has been flooding this country for many months past.”

However, Ernest Blythe made very different proposals to the North East Policy Committee a few days later on 9th August. Instead, Blythe suggested that they should push the IRA and northern Catholics to recognise the authority of the Northern Ireland government and actively support it. However Blythe’s rationale was that the current policy (non-conciliation) was supported by the (anti-treaty) IRA and so the Provisional Government should reverse its position on the north as a way of “…attacking them [the IRA] all along the line.” Furthermore, Blythe wrote, “The ‘Outrage’ propaganda should be dropped in the Twenty-Six Counties. It can have no effect but to make certain of our people see red which will never do us any good.” Blythe effectively proposed sacrificing the book, details of the Belfast pogrom and revealing the truth of what had happened in Belfast since 1920 for tactical reasons during the civil war. Perhaps to test the public reaction, Blythe’s proposals were clearly leaked to some newspapers, such as the Donegal News, which reported them on 12th August as ‘rumours circulating in Dublin’. The leaks claimed they were actually proposals that had been agreed between a northern bishop and a leading British cabinet minister (this may have been mischievous as Blythe, at least, knew that Bishop MacRory had recently met Lloyd George in London). On 19th August the Provisional Government endorsed Blythe’s proposals.

Ernest Blythe

Ernest BlythePresuming Hassan had immediately given his manuscript to the printers, it seems unlikely that it had been composited, printed and bound before either the 19th August when Blythe had the Provisional Government agree to drop it or Collins’ death on 22nd August (Collins was apparently to meet with Alfred O’Rahilly the night after he was killed). As such, it seems likely that the book was literally in the printers when Collins died. Since Collins hadn’t yet challenged other members of the Provisional Government over endorsement of Blythe’s proposals, or had a chance to argue they should be dropped, Blythe’s policy stood and that was the end of Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922. For now.

Hassan’s own obituary in the Irish Independent (5/1/1939) confirms the story but adds a different spin to the reason why the book was censored, “By order of the Provisional Government an edition, running into many thousand copies, was printed for distribution on a world-wide scale, but before the time of publication things in the North took a better turn, and it was decided not to proceed further with it.” Hassan being from Banagher in Derry, he had a lengthy obituary in the Derry Journal (6/1/1939) which also confirms that “…when printed, the publication had been withdrawn…” although the Derry Journal implied that had happened earlier in 1922, during the Craig-Collins talks (which is clearly incorrect based on the content of the book). In a 1970 article in the Irish Examiner (9/9/1970), historian Andrew Boyd was closer to the truth in suggesting that the Provisional Government thought publication of the book “…was more likely to incite war than promote peace.”

While Boyd’s phrasing suggests slightly more altruistic motives, failure to publish the book may have had much more longer term repercussions. Many of the issues raised throughout the book, and much of Hassan’s language, finds dark echoes in the violence in Belfast in 1935 and again from 1969 onwards. Given that between January 1919 and June 1922, around 20% of all War of Independence fatalities occurred in Belfast, the almost absolute absence of meaningful histories of the period in Belfast, until ‘Facts and Figures’ was eventually made widely available in 1997, is still astonishing. A moment, which could have possibly seen some sort of coming to terms with the immediate past in 1922, was entirely missed. Failing to quickly unpack the legacy of 1920-1922 may also have been crucial to creating the type of long-term dynamics around ‘dealing with the past’ that we still see today. While the Provisional Government effectively censored reporting on the violence in Belfast after 19th August 1922, the likes of Belfast Newsletter and Northern Whig could continue, unchallenged, to dismiss accounts of the violence as shameless propaganda.

A final key point, here, is in the use of the term ‘pogrom’ in the books title. In recent decades, historians like Robert Lynch and Alan Parkinson have been at pains to dismiss the use of the term. However, contemporary commentators who had witnessed the violence in Belfast in 1920-1922, had absolutely no qualms about using it. Ironically, the current accepted definition of ‘pogrom’, used by the likes of Werner Bergmann and David Engels, is “…a unilateral, non-governmental form of collective violence initiated by the majority population against a largely defenseless ethnic group”. That collective violence generally manifests as riots and is directed at the minority group collectively rather than targeting specific individuals. There is also an the implication that officials have connived at it, but not directly organised it. This is exactly how Hassan uses the term, but not Lynch or Parkinson [Lynch claims, for it to be a pogrom, victims should be mostly women and children, Parkinson that it should be state organised. Neither interpretation is consistent with current accepted definitions of a ‘pogrom’]. Kieron Glennon, though, thought it appropriate and used the term in the title of his From Pogrom to Civil War.

Today, pretty much no-one will want the term ‘pogrom’ used. But as pointed out earlier, the real moment for coming to terms with all this likely passed with the original suppression of ‘Facts and Figures’ in 1922. Yet Hassan himself makes the most important point of all in his own dedication at the start of the book. Proportionally, very few people took an active part in the pogrom, and of those many were likely caught up in it rather than instrumental in making it happen. Hassan makes that point explicitly at the start of the book, dedicating it to that vast majority who took no hand or part in it: “The many Ulster Protestants, who have always lived in peace and friendliness with their Catholic neighbours, this little book dealing with the acts of their misguided co-religionists, is affectionately dedicated.”

Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922 by G.B. Kenna, in its original cover, is available again now via Amazon.

Kieron Glennon’s From Pogrom to Civil War is published by Mercier Press. The details of Ernest Blythe’s proposals to the North East Policy Committee are included in his papers in UCD (IEUCDAP24) and quoted at length by Glennon.

J. Anthony Gaughan’s biography of O’Rahilly, Alfred O’Rahilly is published by Kingdom Books.

The appropriateness of the term ‘pogrom’ is discussed by Robert Lynch (in his 2008 paper in the Journal of British Studies, “The People’s Protectors? The Irish Republican Army and the “Belfast Pogrom,” 1920-1922”) and Alan Parkinson in The Unholy War (published by Four Courts).

For a discussion of Werner Bergmann’s definition of a pogrom see Heitmeyer and Hagan’s survey paper in International Handbook of Violence Research, Volume 1. David Engels views are reviewed in Dekel-Chen, Gaunt, Meir and Bartal’s Anti-Jewish Violence. Rethinking the Pogrom in East European History.

Thanks to Martin Molloy and Niall Hassan for the photograph of Fr Hassan. Father John Hassan was born in Coolnamon, near Feeney in Derry in 1875 and went to school first at Fincairn, then Ballinascreen, then St. Columbs in 1892. In 1894 he went to Maynooth and then Rome the following year where he was ordained in St John Laterans by Cardinal Respighi on 9th June 1900. He was fluent in Italian, French and German as well as Irish and English. He returned to the Down and Conor diocese in Ireland, serving in parishes in Ballycastle, Castlewellan, Downpatrick and Kilkeel before he was transferred to Belfast, firstly to St Josephs in Sailortown in1910. He moved to St Mary’s, Chapel Lane in 1916 where he was involved in the events described above, staying there until 1929 when he moved as parish priest to Ballymoney were he died in 1939 (from Derry Journal, 6/1/1939).

Andrew Boyd, the historian you cited in your post, certainly used the word “pogram” in speaking and was convinced it was the correct term for what he was describing in e.g. Holy War in Belfast. I don’t know if he used it in his writings

LikeLike

I mention Robert Lynch and Alan Parkinson in use of ‘pogrom’, I didn’t Boyd dismissing it anywhere. He didn’t use the word pogrom in 1969 edition of Holy War in Belfast but he hadn’t access to Hassan’s book either and his account of 1920-1922 is very brief (maybe a page).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the info!

As I said Boyd certainly used the term in speaking.

Being originally from Unionist East Belfast, I suggest he certainly understood the impact of what he was saying.

He was always very cautious in what he wrote, taking a sort of “English Labour ” line (either to avoid problems or because he really believed it, since he was friends with Michael Foot and Tony Benn and contributed anonymously, without retribution to Tribune for many years).

He may well not have used the word “pogram” in his writings.

But I certainly heard him say it and discuss it .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Given he called the book ‘Holy War in Belfast’ he may have gone the other way and thought the word ‘pogrom’ was too tame.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John – our conversation got me thinking. I dug out my copy of Holy War in belfast – It was an 1987 edition (probably the last?). In in Boyd talks extensively of pogroms and quotes Hassan’s work

LikeLike

AFAI remember the title was suggested by his publisher.

Holy War in Belfast was originally conceived as Boyd’s PhD project (Boyd himself told me “I took it on because I realized nobody had ever gone through newspaper reports of what had actually happened” ).

As a mature student , an engineer with a BSc (econ) , a wife and 4 children to suppport, while working and researching a PhD (no grants in them days) and a left-wing “mission” to support, Boyd jumped at the chance to make some money/spread some info with the publication of a book rather than opting for a PhD thesis nobody would have read!

LikeLike

Thank you , Great Post. I Really enjoyed the Read.

Joe French.

LikeLike