In 1992, Mary Kerr was driving along the M2 motorway in Belfast at the point immediately to the east of the former location of an area known as Weaver Street, off the York Road. As the name suggests, Weaver Street had been a residential area largely occupied by mill workers and their families. Kerr later recounted to the Sunday Life newspaper how a fair-haired girl, aged around 11, wearing an old-style dress and without shoes, skipped across the motorway in front of her car. When Kerr looked around to see where she had went, the girl was gone.

One year to the day later, Kerr read an old article which the Irish News had reprinted reporting on girls killed in a bombing in Weaver Street on that day some 70 years previously. Kerr told the Sunday Life, “Instinctively I knew they were connected to what I had seen that night…”[11]

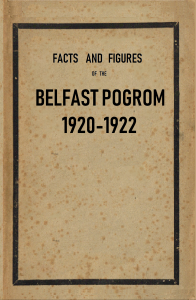

Weaver Street had been the scene of a horrific bombing in February 1922, an event that remained unmarked and largely unremarked in 1993 (and is still barely known today). Little, if any, of Belfast’s dark heritage from 1919-22 is formally commemorated in the city, either, as if events and the violence of those years were somehow just not remembered. Of course, that absence of commemoration is revealing in itself.

Below, I explore events after the Weaver Street bombing using ideas found in studies of my eastern Europe, that of a ‘non-site of memory’ (the origin of the term ‘non-site of memory’ is explained further below). This article also looks at the suitability of the concept to provide insights into the scenes of other significant episodes from twentieth century Irish history, such as the Tuam and Bessborough Mother and Baby Homes, as well as other institutional settings. There may be insights here too into the near future in Gaza, where we may see a similar process of elision and erasure of physical memories of the Palestinians.

It was a French historian, Pierre Nora, who coined the term ‘site of memory’ in 1970 to describe the likes of monuments to the past or archives of historical documents. Nora was trying to understand the past through studying memories of events and how they are used to create histories and (in doing so) influence the world around them. History, and archaeology, and heritage, are regularly used to define and shape values and create a narrative that is intended to legitimize or promote contemporary political ideologies. The phrase ‘site of memory’ is perhaps best explained by the more accurate translation of the French term ‘lieux de mémoire’ as (the more awkward sounding) ‘site of remembering’.[1]

People today are familiar with sites of memory, even if they haven’t heard them described as such. Most modern societies use monuments to commemorate historical events. Some, such as the Whitehall cenotaph in London are, or have become, the setting for annual rituals to display and communicate values to modern audiences (such as trying to evoke former military and imperial glories). These rituals use symbols and imagery that draw upon particular and often partisan readings of history to promote political strategies in the present or future.

Later writers have suggested that the term ‘sites of memory’ should be more restricted in its scope and exclude archives and other spaces where records are brought together. Instead, the likes of Jay Winters have defined sites of memory as “…physical sites where commemorative acts take place…” noting that often, in twentieth century contexts, such sites are associated with wartime violence.[2] Winters goes on to say that sites of memory “…are there as points of reference not only for those who survived traumatic events, but also for those born long after them. The word ‘memory’ becomes a metaphor for the fashioning of narratives about the past when those with direct experience of events die off. Sites of memory inevitably become sites of second-order memory, places where people remember the memories of others, those who survived the events marked there.” Others have noted that ‘sites of memory’ are not necessarily spaces that can be neatly drawn on a map, as Andrzej Szpociński has pointed out some are almost metaphorical ‘places’ with no real specific definition.[3]

One of Pierre Nora’s main interests was in understanding how memory of the past was shaped, transmitted and used by societies. In the 1980s, his concept was explored and inverted by the French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann who also identified ‘non-lieux de mémoire’, or ‘non-sites of memory’ during his work on the landmark 1985 film Shoah which documented the systematic murders of European Jews during the second world war.[4] Lanzmann was referring to places that witnessed past violence but which had been configured to obscure that violence and render them, in effect, invisible to contemporary society. Completely forgotten, and often minimised or excluded from historical accounts, these places and the events that took place there are the antithesis of ‘sites of memory’ that have monuments or plaques or host communal commemorative events.

Such non-sites of memory may even be places at which human remains were still present and may continue to be present. As Roma Sedenkya describes it, these human remains typically “…have not been neutralized by funerary rites” either through performance of religious ceremonies or completion of administrative or legal proceedings.[5] By ‘neutralized’, Sedenkya means the typical ways societies use funerals, formal burial, commemoration and remembering to mark a death and begin or progress the process of grieving and recovery after a loss, which often has huge emotional and psychological value to families and communities. Obviously the lack of those rites, then, can delay or inhibit any such recovery. These non-sites of memory often have particular characteristics, such as having been abandoned, an absence of memorial markers and possible evidence of reactions of fear and shame.

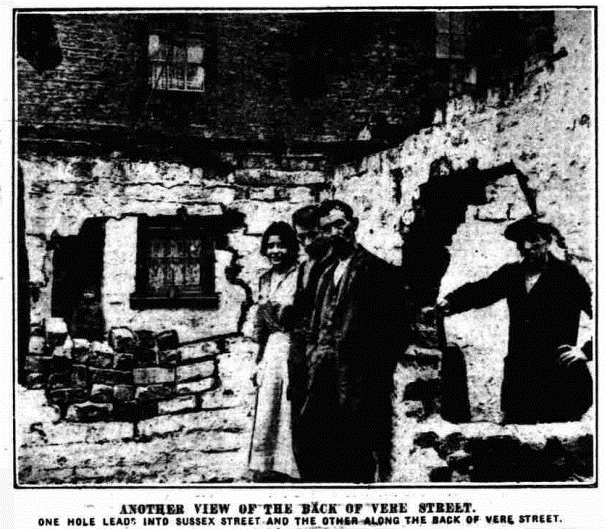

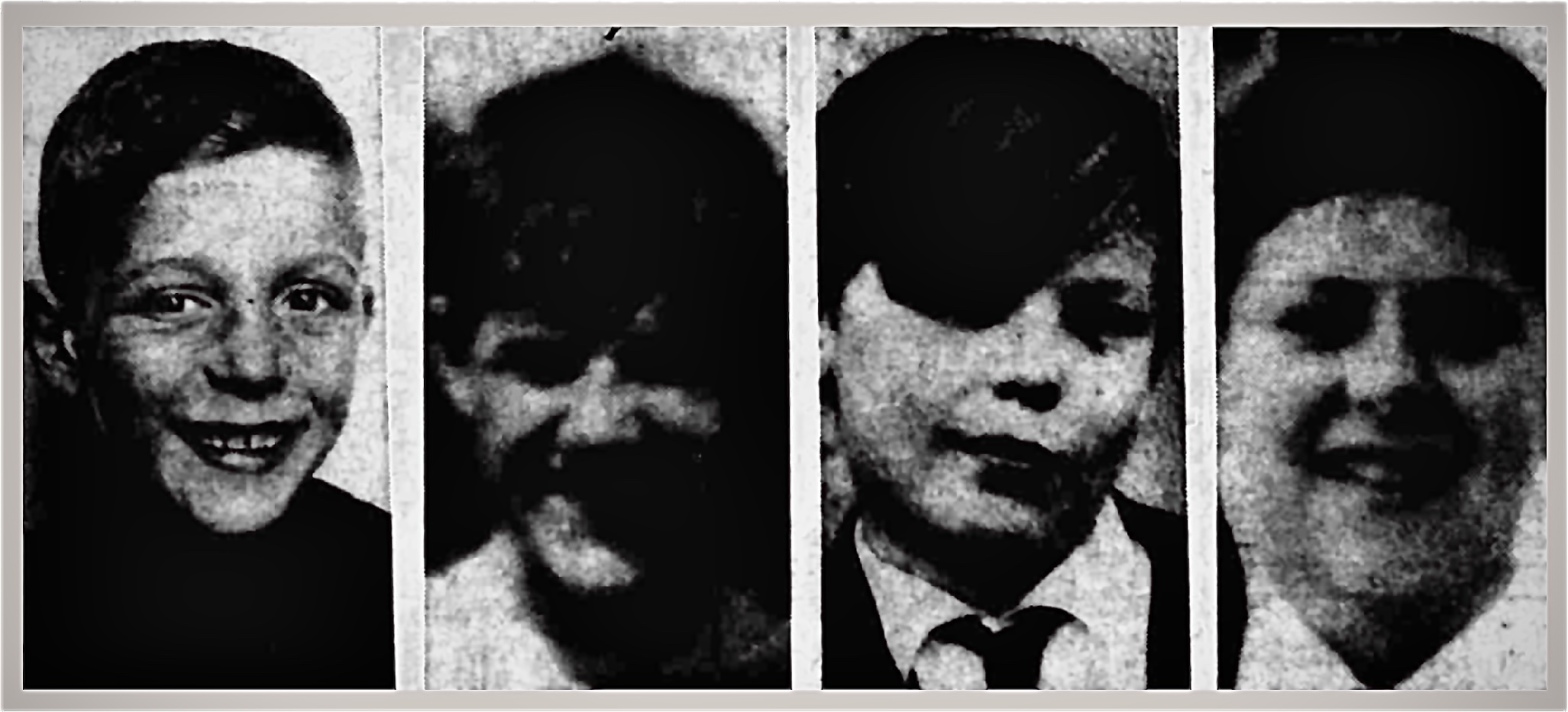

On February 13, 1922, Weaver Street was the scene of an act of violence that Winston Churchill described as the “…worst thing which has happened in Ireland in the last three years”. That day, a man in a police uniform directed Catholic children in adjoining streets to go and play as a group in Weaver Street. Two other men then appeared and chatted to other men in police uniforms, before one threw a bomb into the middle of the children who were playing 20-30m away.[6] The men then opened fire on people that come out of their houses to try and help the wounded and dying. Six died including four young girls, while more than twenty children were wounded (including a girl named Mary Kerr). Some were left with life changing injuries. An incident in the adjoining Milewater Street, months previously, had also led to a number of children being wounded by gunfire.

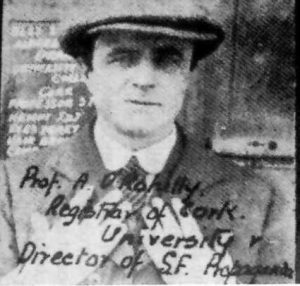

Three months after the bombing, in May 1922, any Catholic residents who had remained in the area were forced to flee (around one hundred and forty-eight families). At a coroner’s hearing on the bombing victims, residents identified the role of policemen in the bombing itself and failures to gather evidence or investigate the attack. The Unionist government’s press office also issued disinformation to mislead about the nature of the bombing and identity of the victims. Today the street itself no longer exists on the map of Belfast and an event deemed to be the “…worst thing which has happened…” barely features in histories of the period, or – in 2022 – as part of the Decade of Centenaries programmes that remembered events from 100 years previously.

So, should we regard Weaver Street as a ‘non-site of memory’? Claude Lanzmann and later scholars like Roma Senedyka used the concept of non-sites of memory in an attempt to find language that might describe aspects of the horrific violence inflicted on European Jews in the 1930s and 1940s and the subsequent history of those locations where the violence took place. Since then Pierre Nora’s original concept, ‘sites of memory’, has been used to explore locations as far apart as Georgia and Chile.[7] But can the same be done with ‘non-sites of memory’?

In the case of Weaver Street, some of the basic characteristics are clearly present such as a lack of physical recognition at the site. And this is reinforced by noting that an absence of memorialisation to victims of the period is not universal. Six victims of a massacre at Altnaveigh, near Newry in June 1922, were already commemorated with a memorial by the following summer.[8] An obvious contrast here, reflecting the interests of the post-1921 Unionist government in Belfast, being that the victims at Altanaveigh were Protestants killed by an IRA unit under orders given by Frank Aiken (later a senior figure in the government in Dublin), while those at Weaver Street were Catholic.[9]

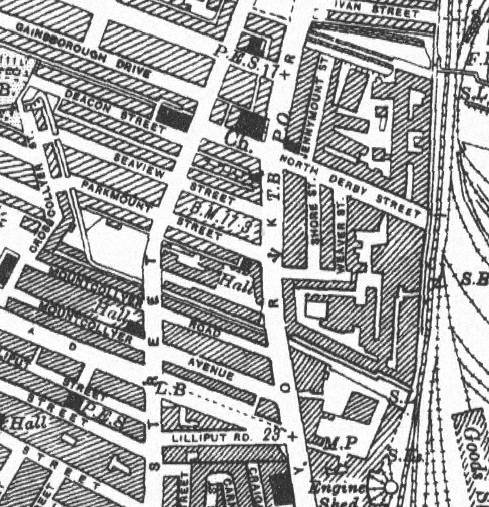

After being forced from the area in May 1922, the Catholic residents of Weaver Street and surrounding streets were dispersed over a variety of locations, typically within other districts in Belfast with substantial Catholic populations. Their former houses were then occupied by Protestant families. The Catholic residents mainly fled to areas in north Belfast and in west Belfast. Some families retained memories of the violence but in other cases relatives of the dead had heard little of the events.[10] In the summer of 1932, ten years after the bombing, Belfast’s main unionist newspaper, the Belfast Telegraph, could carry a photograph of Weaver Street decked out in flags at the main annual event celebrating Protestant hegemony. The photograph is positioned in the centre of a single page photographic spread. Of all the places in the area, on a number of occasions Weaver Street was selected to host election rallies and other unionist political gatherings in the 1930s.

Over the course of the decades between 1922 and the 1990s, the area between between York Road and the railway line, including Weaver Street, Shore Street, most of Milewater Street and some of North Derby Street were gradually absorbed into a factory complex and the streets removed from the map of Belfast by the end of the 1960s. Every other street between York Road and the railway line present in the 1890s is still there today. In the background of a photograph showing Shore Street being demolished in the late 1950s someone has painted ‘No Pope Here’ on a wall. Weaver Street survives, in an archaeological sense, below ground beneath the factory complex and the position of Weaver Street itself remains echoed in the alignment of today’s buildings.

Today, it is possible for someone to walk down North Derby Street as far as the large factory building and turn and look along the front elevation of the building. This elevation stands over the former façade of the little red brick houses of Weaver Street. The view is partially obscured by fencing and (until recently) vegetation, and the fencing itself means it is not possible to walk along what was Weaver Street. The only publicly accessible space today is the exact spot from which a man threw a grenade into a group of children playing only yards away in 1922.

In terms of assessing the applicability of transposing Lanzmann’s non-lieux de mémoire concept to Ireland, these elements of the Weaver Street story resonate with other characteristics of non-sites of memory that Roma Senedyka identifies, including that “…the victims typically have a collective identity (usually ethnic) distinct from the society currently living in the area, whose self-conception is threatened by the occurrence of the non-site of memory. Such localities are transformed, manipulated, neglected, or contested in some other way (often devastated or littered)…”.[12] This suggests that the approach can help provide a framework in which it may be possible to begin to interrogate the wider questions around how such events were remembered, or forgotten or ignored, and what conclusions we might draw from that.

This concept of non-sites of memory may also be usefully transposed to other locations in Ireland, particularly twentieth century sites such as Tuam and Bessborough.[13] Both were ‘Mother and Baby Homes’ where many of the characteristics of non-sites of memory can be recognised, particularly if Senedyka’s sense of collective identity is defined as including ideas of gender and social class. In both cases, the presence of human remains at the sites, the subsequent treatment, remembering and forgetting of those buried there could be explored and understood in a framework drawing upon the characteristics of non-sites of memory. Assessing the subsequent histories of sites like Tuam and Bessborough through the prism of non-sites of memory may then be a useful narrative tool to explore how contemporary society viewed and understood them. It may also help develop language which former residents and those who have family members who were resident can use to talk about the experience.

[1] Nora, Pierre 1974 Mémoire collective in Faire de l’histoire. Le Goff, Jacques and Nora, Pierre (eds). Paris: Gallimard.

[2] Winter, Jay 2010 Sites of Memory in Radstone, S. and Schwarz, B. (eds) Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, pp.312-324. Fordham. Winters also discusses the use of cenotaphs and the longer quote in this paragraph in the same paper (p.313).

[3] Szpociński, Andrzej 2016 Sites of Memory. Teksty Drugie 2016, 1, pp.245-254

[4] See Lanzmann, C. and Gantheret, F. 1986 L’Entretien de Claude Lanzmann, Les non-lieux de mémoire. Nouvelle Revue de Psychanalyse 33, pp.293–305.

[5] See Sedenyka, R. 2021 Sites of violence and their communities: critical memory studies in the post-human era. International Journal of Heritage, Memory and Conflict 1, pp.1-11.

[6] See https://treasonfelony.wordpress.com/2016/02/04/the-weaver-street-bombing-and-not-dealing-with-the-past/

[7] Marszałek-Kawa, Joanna and Ratke-Majewska, Anna 2016 Anna Sites of Memory in the Public Space of Chile and Georgia: the Transition and Pre-Transition Period. Polish Political Science Yearbook, 45, pp. 99–116.

[8] Northern Whig August 27, 1923

[9] See Knipe, Gregory 2019 The Fourth Northerners. Litter Press.

[10] Karl O’Hanlon, pers. comm. (great nephew of one of the victims, Eliza O’Hanlon); thanks also to nieces of Florence Sheridan and Maggie Sheridan who had been wounded (aged 19 months and 6 years) by a bomb thrown into a group of children playing in Milewater Street, adjoining Weaver Street on 25 September 1921, they recalled their aunt was still able show them the wounds in her old age.

[11] Sunday Life, June 27, 1993.

[12] Sendyka R. 2016 Sites That Haunt: Affects and Non-sites of Memory. East European Politics and Societies, 30(4): p.700.

[13] See Irish Examiner, March 11, 2017.