Fifty years ago this summer peace lines were erected across parts of Belfast, most famously along a line that roughly follows the course of the River Farset from Divis Street to the Springfield Road. Here, I look at how it was first built in September 1969 and some of its predecessors in Belfast. I also take a look at the coincidence of its location and the River Farset.

It is often overlooked that the British Army had been deployed in Belfast before August 1969. It had initially been used to guard infrastructure and key installation in April 1969 in the face of an ongoing unionist bombing campaign. That deployment was then extended in mid-August due to the rapidly intensifying violence which led to the widespread erection of barricades by residents in various districts in Belfast (a book on the violence that summer – Burnt Out – has just been published by Michael McCann).

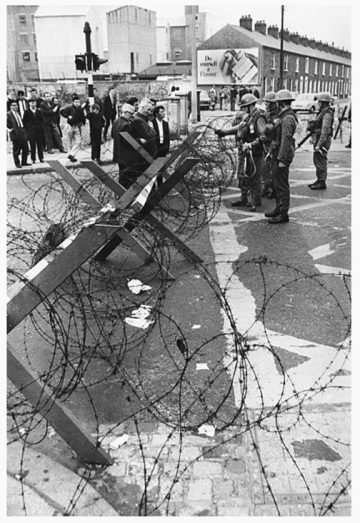

Military barrier of ‘knife rests’, 16th August, 1969 (Getty Images)

Immediately troops were on the streets, many public figures pressed for the removal of the barricades as a symbol of a return to normality. A short term solution to this was to replace the physical barriers with soldiers, what was described in conversation between Irish diplomat K. Rush and Sir Edward Peck of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office as a ‘human barricade’. While the Irish representatives made it clear that it believed that the ‘human barricade’ was preferable to physical alternatives, Peck implied there was a need for a physical barrier due to British soldiers being a ‘scarce commodity’. Photographs from 15th and 16th August 1969 show the interim measures put in place along side the military – mainly portable wire obstacles, such as knife rests, in place at various locations. After discussions over the replacement of barricades between community leaders, the IRA and the British Army there were tentative moves to start dismantling and replacing the residents’ ad hoc barricades. These took many forms, including everything from burnt out vehicles to solid barriers of broken paving stones to shuttering erected on scaffolding. Immediately the British Army was to replace the ad hoc barricades with knife rests, which in ‘Catholic’ districts, were to be jointly guarded by the British Army and Citizen’s Defence Committee.

On 9th September, the Unionist Prime Minister Chichester Clarke met with his Joint Security Committee at Stormont Castle, including the Ministers of Home Affairs, Education and Development, the Army GOC and Chief of Staff and various RUC, Army and Civil Service figures. The conclusions from the meeting noted that “A peace line was to be established to separate physically the Falls and the Shankill communities. Initially this would take the form of a temporary barbed wire fence which would be manned by the Army and the Police. The actual line of fence would be decided in consultations with the Belfast Corporation. It was agreed that there should be no question of the peace line becoming permanent although it was acknowledge that the barriers might have to be strengthened in some locations.” That opening phrase ‘peace line’ now entered the security lexicon, although ‘peace wall’ was occasionally, if more rarely, used (prior to 1969 the phrase ‘peace line’ was generally just associated with the demarcation line from the end of the Korean War).

That evening, Chichester Clarke made a broadcast that was televised on the news on BBC, UTV and RTE (you can watch it and other footage of the peace lines being constructed here). He stated that: “We have now decided that the army will erect and man a firm peace line to be sited between the Divis Street area and Shankill Road on a line determined by a representative body from the city hall. In conjunction with this action, barricades will be removed in all areas of Belfast, both Protestant and Catholic.” The initial reaction from representatives of the ‘Catholic’ residents was very negative.

The knife rests and residents’ barricades were thus to be replaced with wire entanglements straight out of the British Army’s Manual of Fields Works (All Arms). The first to be erected were constructed of barbed wire strung between multiple bays of pickets. The pickets were placed in holes drilled through the road surface and then hammered into place (as shown in the photos below). Wire was then strung between the pickets to create the required obstacle. As they were solely composed of pickets and wire, they controlled movement but did not create a visual barrier. The construction of the peace line at the corner of Cawnpore Street and Cupar Street on 10th September 1969 is shown below (taken as stills from television footage).

The ‘representative body from city hall’ that was going to determine the route was to be chaired by the Lord Mayor, Alderman Joseph Cairns. It included all the councillors from the wards involved (this is based on reporting in the Irish Press 11/9/1969 and contemporary television footage and interviews). This body was to identify where to locate the ‘peace line’ street by street. The start and end points were largely self-defined by flashpoints and the rioting of the past weeks. However, negotiating the exact position often involved arguing over (literally) which individual houses it needed to accommodate on the Falls Road/Divis Street or Shankill Road side of the line.

The actual construction works were undertaken by British Army Engineers escorted by the 2nd Grenadier Guards and began at about 4.30 pm at either end, starting in the east at Coates Street (which was closest to the Millfield/Divis Street end) and in the west from the Springfield Road end of Cupar Street. In theory, work was to progress towards a centre point on the route agreed by the working group. Initially installing the peace line seems to have stopped at 9 pm on the 10th September and then resumed again at 8 am on 11th (these times are quoted in the press on 11th September). Despite the intention of the western and eastern sections converging, progress at the eastern end was obstructed by a failure to agree the position of the wire entanglement on Dover Street and it was the last to be completed. According to The Irish Press (11/9/1969), on the first day work had begun with rival crowds singing “Go home you bums, Go home you bums…” to the soldiers involved.

Photos of the peace line just after it was constructed on 10th/11th September at Cupar Street and Lucknow Street are shown below (from Irish Independent 11th and 12th September 1969).

The immediate impetus for the erection of the ‘peace line’ was presumably as preparation for violence that was expected to accompany the imminent release of the Cameron Report (on the circumstances that led to violence the previous year). There had been leaks since early September that signalled that the report would be critical of the Unionist government and the RUC. This was confirmed when it was published and widely discussed in the media on the 11th and 12th September. However, reactions to the Cameron Report, in particular recommended changes to the RUC meant that the ‘peace line’ did not stop violence continuing.

Newspapers reports on 26th and 27th September show how the night of the 25th September had quickly exposed the limitations of the wire entanglements as a ‘firm peace line’. In Coates Street, a crowd from the Shankill Road side simply threw petrol bombs over the ‘peace line’ and burned out a number of houses. Repeated violence in Coates Street and Sackville Street also saw crowds breach the wire entanglements to attack houses on the other side of the peace line.

The failure of the ‘peace line’ had clearly been noted by the military. The Belfast Telegraph had reported on Wednesday 24th September that the British Army had been removing residents’ barricades by agreement and only a handful were left. The paper noted that “As far as West Belfast is concerned, some of the heavy steel ones are remaining for a few days until the Army replaces them with special corrugated iron affairs that will foil snipers and stop cars speeding up and down the streets.” By the weekend of 27th-28th September it was abundantly clear that the tactics employed by crowds attacking from the Shankill Road side were exposing the frailty of the ‘peace line’. Just as the wire entanglements were merely being pushed aside, soldiers were carrying rifles with live ammunition and, at this date, simply stepped back rather than open fire on the crowd. Contemporary accounts clearly show that the troops had been deployed without either training or suitable equipment for crowd control (apart from CS gas). Similarly, the wire entanglements were completely ineffective as obstacles when it came to snipers and missiles.

By Monday 29th September British Army engineers had begun to erect ‘concertina-type’ barriers in Coates Street/Sackville Street (eg see Belfast Telegraph 2/10/1969). The authorities also announced tactical changes in how the British Army would deal with rioters, including an acknowledgement of the passive role taken by the Army to date, such as when soldiers stood aside while rioters entered and burned houses in Coates Street. It claimed that some soldiers would now be deployed without guns but with two foot batons instead. The ‘concertina-type’ barriers that were to replace the wire entanglements would be fifteen feet in height and would completely seal off the ends of individual streets (the same reports in Belfast Telegraph dismiss claims that the peace line was to be extended to fifty feet in width). The new barriers were constructed from corrugated iron sheeting erected on wooden studding. Photographs from Coates Street show the first of these being constructed (Getty Images). They appear to be closer to around ten feet in height that the proposed fifteen feet.

The completed concertina-type barrier, with a reinstated wire entanglement obstacle in front of it, is visible in this photograph taken in December 1969 (Getty Images).

Questions to the Unionist Minister of Home Affairs at Stormont, Robert Porter, from Unionist MP Norman Laird indicated that it was the Minister of Home Affairs who had the authority to close roads (Stormont Hansard, 2/10/1969) and that the concertina-type barriers were erected by the Army with Porter’s agreement (see Stormont Hansard 7/10/1969). In the latter debate, Porter stated that the corrugated iron barricades were intended to be purely temporary. Fifty years later the peace line and many others still remain. Ironically, though, none of the current peace-line appears to contain any surviving sections of the first ‘concertina-type’ barrier.

The practice of physically segregating districts and individual streets in Belfast was not new in 1969. When intermittent violence throughout the early 1930s peaked on 12th July 1935, British soldiers were deployed to act, initially, as a ‘human barricade’. As that violence continued to escalate quickly, in particular in York Street and Sailortown, on 16th July the RUC began erecting physical barriers by closing off the end of streets with hoardings including New Andrew Street, New Dock Street, Marine Street, Ship Street, Fleet Street and Nelson Street. This was then extended to streets in the Old Lodge Road by the 19th July (eg see Belfast Newsletter 17/7/1935, Northern Whig 19/7/1935). These were ‘concertina-type’ barriers, made of corrugated iron and seven feet in height (eg see description in Irish Times, 30/4/1936). Despite continued protests from businesses in the area, they were only taken down in the middle of June 1936 (see Northern Whig, 13/6/1936). Notably, some residents claimed that the barriers had been unwanted as they simply prolonged and reinforced division (eg the likes of Jackie Quinn, quoted in Munck and Rolstons’ Belfast in the Thirties: an Oral History).

The barrier on New Dock Street is shown below (from Irish Press 19/7/1935, for more see here).

Prior to 1935, the same ‘peace line’ structures had been also used during 1920-22. This included all the same elements that were to be found in 1969: human barricades, knife rests, wire entanglements and hoardings. The latter two are recorded in Ballymaccarrett in particular. The Belfast Newsletter reported on 24th July 1920 that Seaforde Street and Wolff Street had been closed with wire entanglements the previous day. Two days later the paper reported that sandbagged and wire barricades had been put in place at Seaforde Street, Short Strand, Middlepath Street, Lackagh Street, Harland Street and Wolff Street. Timber barriers were then erected at the Newtownards Road end of Seaforde Street and Young’s Row in early March 1922 (see Belfast Newsletter 13/3/1922). Despite continued opposition, the barriers at the end of Seaforde Street and Youngs Row were only taken down towards the end of 1923 (newspaper reports in the summer of 1923 clearly show the barriers were erected on the authority of the Minister of Home Affairs). The sequence of wire entanglements, knife rests and timber barriers being put up and taken down at Seaforde Street is shown below (from various sources: Illustrated London News 4/9/1920; cartoon from Illustrated London News 31/7/1920; Sunday Independent 4/12/1921; construction timber barrier, March 1922, from here; timber barrier being removed in 1923 from Snapshots of Old Belfast 1920-24, by Joe Baker, 2011).

There were also sandbagged military posts and wire entanglements at various other locations around the city. A Dáil Publicity Department Communication published by the Irish Independent on 22nd June 1922 described how “There is now a fort or blockhouse on the Sth African system along every 100 yards of Falls Road. The windows are sandbagged and wired.” A still from a Pathé newsreel of Belfast in 1922 is shown below. The reference to the South African system was clearly intended to invoke a tactical comparison with the blockhouses and concentrations employed by the British Army during the Second Boer War and other newspaper reports make reference to the tactics deployed then in Transvaal.

The picture below (from Getty Images) shows a sandbagged blockhouse in Belfast at an unspecified location (possibly opposite Falls Park) in 1920. While the file is dated 1st January 1920, it says on ‘Orange Day’ which seems to mean 12th July 1920.

Finally, it is interesting to look at the physical location and course of the peace line (see map). Belfast in Irish is usually rendered as Beal Feirste and which is assumed to derive from its location at the mouth of the River Farset which enters the Lagan at High Street (the Farset seems to take its name from sandbanks where it enters the Lagan). A fourteenth century borough was founded where the Farset, Lagan and various routeways converged, with the layout of High Street, Ann Street and the various entries likely dictated by the layout of the medieval borough’s property boundaries. An earlier church site at Shankill lay alongside a ford over the Farset as it flowed down towards the Lagan (at today’s Lanark Way/Shankill Road junction). The name Shankill (Sean Cill or ‘old church’) shows it predates a later church, known in the seventeenth century as the Corporation Church, that lay close to where St George’s is today on High Street. Pre-seventeenth century documentation of Belfast is so inadequate that a handful of reference to a ‘chapel of the ford’ are usually taken to mean another church that predates the Corporation Church, but the ‘chapel of the ford’ but could equally be referring to Shankill (given that it also sat on a ford over the Farset).

Where north and west Belfast slope down to the Lagan there are various streams and rivers that could be damned to power mills and factories, attracting industry and drawing workers in from the countryside. This led to the growth of industries and residential areas for the workers on this side of the city. The Shankill Road and Falls Road, which converge along the Farset, drew in workers to the factories, mills and foundries that established in an industrial district along the banks of the Farset itself. Religious and ethnic tensions were constantly preyed upon, arguably to the benefit of the factory and mill owners who could play on sectarian fears to deflect from poor work and housing conditions. The communities that then grew along both the Shankill and Falls Road, on either side of the River Farset, tended to have greater proportions of Protestants (Shankill) and Catholics (Falls) as intermittent violence throughout the nineteenth century often lead to sporadic increases in segregation (and thus perpetuated the tensions). The final expression of this appears to be the tracing of the ‘peace line’ in September 1969 along a route that mirrors that of the Farset itself.

You can read more about the summer of 1969 in Michael McCann’s bookBurnt Out and about the wider background (for free for the next few days) in Belfast Battalion.

A current project by James O’Leary of University College London is documenting the peace walls at http://www.peacewall-archive.net which can be viewed here.

2 thoughts on “The start of the peace lines: Belfast, 1969.”