In 1972, an IRA hunger strike was successful in achieving the recognition of the political status of those held as prisoners by the British government. The hunger strike provided significant lessons for later republican protests in 1980 and 1981 and, in itself, was modeled on earlier hunger strikes.

The numbers of prisoners had increased dramatically since 1969, when a wave of detentions in August had preceded the burning of Bombay Street by unionists. Two of those detained were interned until later that year, foreshadowing the widespread use of internment to repress opposition to the northern government from August 1971.

From August 1971, there was a constant increase in the numbers held at Belfast Prison (Crumlin Road), Armagh Gaol, the Maidstone prison ship and the camps at Magilligan and Long Kesh. Many of those detained had been imprisoned by the northern government on one or multiple occasions from the 1920s to the 1960s. Collectively there was a deep well of knowledge of dealing with the systems the northern government deployed to keep its opponents in captivity. This included forms and modalities of protest and resistance, such as hunger strikes.

Republicans had participated in various forms of hunger strike against the northern and southern government in the previous thirty or so years. Open-ended group hunger strikes had taken place in 1936 (in Crumlin Road), 1939-40 in Mountjoy and 1940 and 1941 (in Crumlin Road), 1943 (in Armagh) and 1944 (in Crumlin Road). In 1939, republicans had gone on hunger strike to pressure the southern government, successfully, for release from captivity. In 1940 republican hunger strikes had saw two fatalities, Jack McNeela and Tony D’arcy, but had achieved recognition of their political status by the southern government.

Token, or defined period hunger strikes had also taken place at times (either in solidarity with other protests, or to disrupt the prison system), such as in Crumlin Road in January 1942 and November 1943. They had also taken place more recently, such as on the Maidstone prison ship in 1971. There were also solo hunger strikers, like Paddy Cavanagh in 1935, Sean McCaughey in 1946 (in Portlaoise) and David Fleming in 1946 and 1947. Notably Fleming’s was in parallel with Sean McCaughey’s. He had died quite quickly in Portlaoise after he also refused water as well as food. That tactic dramatically accelerated the point at which a crisis would arise.

A long debate about a hunger strike in D wing of Crumlin Road in 1958-59, ultimately ended in the IRA’s Army Council refusing to endorse such a protest. Many of the senior IRA figures inside and outside Crumlin Road in 1958-59 had been active during the 1940s and were only too aware of the risks and variables that would dictate the likely successful or failure of a hunger strike.

Various initiatives proposed by the IRA leadership in 1971 and 1972, which included ceasefire proposals also called for the release of all ‘political prisoners’. During 1938-45 and 1956-61, when there was widespread use of internment without trial by the northern government, those held as ‘internées’ were accorded special status. As IRA proposals referenced ‘political’ prisoners, there appears to have been a growing consciousness that those awaiting a formal trial or who had been given a prison sentence might be deemed to be outside of this framework, since this happened in 1945 and again in 1961. Senior IRA figures held in Crumlin Road in 1972, like Billy McKee and Prionsias MacAirt, had been present at the time of the releases in 1945 and again in 1961.

Many of the conditions that had limited the effectiveness of previous hunger strikes were not present in 1972. There was a significant level of overt public support for the IRA and the publicity tools that the IRA had access to, such as Republican News, and international media coverage, offered much greater leverage than had been available in the past.

That said, the hunger strike began on 15th May 1972 with little fanfare. This was down to the lack of any real advance notice as, apparently, the IRA inside Crumlin Road had only notified the outside leadership of their intentions on 10th May (it also leaked into the media almost immediately), even though there had been an ongoing protest inside the jail. The first group to join the hunger strike included Billy McKee, Kevin Henry, Malachy Leonard, Martin Boyle and Robert Campbell. The hunger strike cut across high level contacts between the IRA and British government as the Army Council sought to illustrate its capacity to command and control IRA operations through implementing (and insisting on strict observation of) a ceasefire. Brief reports of a possible IRA ceasefire were mentioned by the press during late May, adding further pressure on the authorities to find a settlement to end the hunger strike. Based on previous hunger strikes, the critical period when a hunger striker was going to be at risk of dying, would be around 50 days, which would be early July.

There was a short article about the hunger strike inside the 18th May 1972 edition of Republican News. It mainly quoted Action, a newsletter published in Newington, which “…British justice finds political prisoners: – ‘Guilty’, British justice finds internees – ‘Guilty’. Are they then willing to release only internees? What is the distinction between ‘Guilty’ and ‘Guilty’? The distinction is this: – There has never been enough clamour for the release of ALL. Amnesty is often considered only in terms of internees. THE ‘GUILTY’ MUST BE FREED WITH THE ‘GUILTY’.”

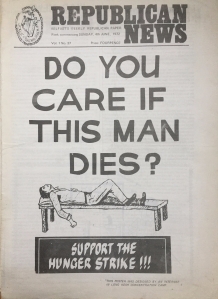

The format of the hunger strike followed that used in the open-ended hunger strike of 1944, as small groups joined at intervals. Unlike 1944, when external publicity was frequently outdated and inaccurate, Republican News could now provide an effective platform for the hunger strikers to increase pressure on the British government. By the next issue, Republican News covered the hunger strike on its front page, stating that it was “…breaking the wall of silence that has been maintained by the authorities…”. This wasn’t strictly true, as the press had issued some reports on the hunger strike, such as nationalist MPs and senators calls on 22nd May to grant political status. The same day, a second team had joined the hunger strike, including Tony O’Kane, John Cowan, Malachy Cullen, Billy McGuigan and Paddy Monaghan.

On 25th May, it was announced (by the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau) that McKee was also now refusing liquids. If the authorities had anticipated some time to review their options, until mid or late June, McKee’s thirst strike meant a crisis could arise in the first week of June. The IRPB statement pointed out that a thirst strike could be fatal after seven or eight days. That weekend, there were twenty-four and thirty-six hour hunger strikes held at various towns and cities in Ireland, Britain and the US in solidarity with those in Crumlin Road. They were also joined by hunger strikers in Armagh jail, the Curragh and Mountjoy.

That Friday (26th May), the southern government re-instituted Special Criminal Courts and carried out a wave of arrests of senior republicans, including leaders of Sinn Féin. Ruairi Ó Bradaigh and Joe Cahill, who were arrested as part of the swoop, went on hunger strike in protest. Now, both the southern government and British government faced hunger striking republicans. On the 29th May, the ‘Official IRA’ called a ceasefire. This coincided with reports that the ‘Provisional’ IRA was considering a ceasefire.

The same day, a third team joined the hunger strike in Crumlin Road, including Ciaran Conway, Gerard McLoughlin, Michael McCrory, Tony Bradley and Noel Quigley. A team had also joined the hunger strike in Armagh jail on 25th May, including Seamus Connelly, Hugh McCann, Tom Kane, Jackie Hawkie, John Haddock and Tom Kearns. Susan Loughran, also in Armagh jail, now joined the hunger strike on 30th May. At the start of June, more female sentenced prisoners in Armagh would join the hunger strike in solidarity, as would internees in Long Kesh. Public hunger strikes in solidarity, petitions and calls from individuals and organisations to grant political status continued to make the news.

By that weekend, McKee had once again begun to take liquids but Kevin Henry, who had started the hunger strike with McKee, had become so weak that he once again began to take food. Unlike previous hunger strikes, the republican O/C in Crumlin Road, Prionsias MacAirt, could have statements carried in the press clarifying misinformation about the progress of the hunger strike. Claims that Billy McKee had ended his hunger strike on 30th May and that the hunger strikers had abandoned the protest on 1st June were immediately dismissed by MacAirt and the IRPB by the next day.

By the 6th June, Billy McKee was so weak that he was confined to his cell. Robert Campbell, who had also been on hunger strike since 15th May, was removed to the Mater Hospital the same day. Reports of Campbell’s condition apparently sparked riots in the New Lodge Road area, but on the morning of the 7th June he was sprung from the hospital by the IRA. The next day, the British government’s Minister responsible for direct rule, William Whitelaw, faced awkward questioning in the Commons over the escape and hunger strike and stated that the British would not be blackmailed.

On the 11th June, Brian McCann, Liam O’Neill, D. Power, Hugh McComb and Denis Donaldson joined the hunger strike. By now there were eight women in Armagh who had joined at a rate of one a day after Susan Loughran, including Margaret O’Connor, Brenda Murphy and Bridie McMahon. A full list of women participating does not seem to have been published although press statements referred to ‘all eight sentenced women’ in Armagh. There were also forty internees in Long Kesh on the protest in solidarity (listed in Republican News, June 11th 1972). Later press reports would claim up to eighty internees were taking part in hunger strikes.

The condition of the hunger strikers was often unclear in press reports, with conflicting reports in the press on whether Malachy Leonard and Billy McKee had been moved to Musgrave Park military hospital. However, there was significant co-ordination of related protests by republican, with the image on the front of Republican News on 4th June featuring as a poster and placard at protests, as well as regular press statements being issued from the Kevin Street offices of Sinn Féin in Dublin.

Behind the scenes, contact between Whitelaw and the IRA leadership saw the SDLP taking on the role of facilitators to try and arrange a direct meeting. The IRA had offered a ceasefire in return for some pre-conditions, which included the granting of political status. The IRA made its position public on 13th June at a press conference in Derry. Behind the scenes, for the next week, the SDLP attempted to broker a meeting between Whitelaw and the IRA against a backdrop of reports on the worsening condition of McKee, Leonard and Boyle. A foretaste of what might happen in the event of the fatality was seen on the day of the IRA statement in Derry, when rumours spread in Belfast that Billy McKee had died and led to widespread rioting in the city.

In late June, press reports also listed ‘Official IRA’ prisoners who had joined the hunger strike, starting on 22nd May (Peter Monaghan and Pat O’Hare), 29th May (Sean Bunting, Mick Mallon, Seamus Carragher and Franky McGrady), 4th June (Brendan Mackin, Artie Maguire, Gerry Loughlin, Jim Robb and Sam Smith) and 11th June (Jim Goodman, Peter O’Hagan and Frank Quinn).

Whitelaw finally agreed to the preconditions on 19th June. That night word reached the hunger strikers in Crumlin Road. As this included political status, a discussion late into the night followed with an agreement to end the hunger strike in Crumlin Road early on the morning of the 20th June. Billy McKee was finally moved to hospital that day. The same day, Joe Cahill ended his hunger strike in Dublin as he was released without charge by the Special Criminal Court (Ó Bradaigh had already been released a week earlier). As news reached Armagh and Long Kesh, those on hunger strike there also ended their protest. In Armagh, the end of the hunger strike was delayed until 21st June as the British hadn’t made clear that the same status would be extended to women prisoners there. Press reports claim it took an additional twenty-four hours to clarify the issue.

The 1972 hunger strikes represent the template adopted for the republican hunger strikes of 1980-81, in terms of the tactical approach, public protest and publicity strategies, particularly in 1981. There were to be subsequent major hunger strikes, including the group hunger strike of 1974, in which Michael Gaughan died and were the strikers were force-fed, and, the solo hunger strike in which Frank Stagg died in 1976. While neither the group that embarked on the open-ended hunger strike of 1980 or the individuals who joined at intervals in 1981 strictly followed the same format as 1972, the co-ordination of publicity and the scale of the protest bear closest parallels to that of 1972 from which (as from other protests in between) lessons were clearly applied in 1980-81. The 1972 hunger strike itself, though, was modelled on experiences gained by republicans over the 1930s and 1940s. Where the earlier hunger strikes were not successful, the success of the 1972 hunger strike may have been central to the hope, after 1972, that the tactic would work again.

6 thoughts on “The 1972 hunger strike”