The following article looks at sectarian violence in Belfast around the Twelfth in 1935 and the (apparently) coordinated raid by De Valera’s own special police on a Belfast IRA training camp in County Louth. It includes a brief chronology of sectarian violence in the summer of 1935 in the lead up to the Twelfth that was published in 1936 under the pen name ‘Northman’. It appeared in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, entitled ‘The Present Position of Catholics in Northern Ireland’ (the original can be accessed here).

Northman chronology of events:

May 6: Bands were playing all the evening, shots were fired into the house of a Catholic, another Catholic, a woman, was wounded in Earl Street ; windows in St. Joseph’s Club (Dock Street were smashed ; in the early hours of the morning terror reigned in the Antrim Road area due to the activities of some 300 hooligans ; fighting followed ‘band’ activities at Peter’s Hill.

May 9: A Catholic was shot through the stomach in Nelson Street; another Catholic was savagely beaten in Henry Street ; Catholic girls returning from work in mills were chased by a Protestant mob, which attempted to invade Pilot Street (a Catholic area) ; general intimidation of Catholic workers began openly; Catholic women workers were compelled to leave Linfield Mill owing to the hostile attitude of their Protestant fellow-workers and of the crowds in the street outside.

May 10: Catholic workers were threatened and insulted on their way to work; a savage mob turned its attention to the Donegall Road area; owing to state of the city curfew was imposed.

May 23: Mr. William Grant, M.P., was promised by the Minister for Home Affairs that, “if any member of the Royal Ulster Constabulary exceeded his duty,” disciplinary action would be taken. The question arose out of a complaint that the police had acted too drastically in restraining rioters in Grove and Vere Streets (Protestant areas). It is unnecessary to remark that the police did not afterwards “…exceed their duty…” but acted with that ‘forbearance’ for which they were commended by Lord Craigavon.

May 30: Meeting of the Ulster Protestant League in Templemore. Avenue, at which the speakers and the audience lustily ‘kicked’ the Pope. After the meeting a rowdy ‘procession’ of the usual type marched to the centre of the city, and from this “procession a bomb was thrown into the Catholic area of Short Strand.

May 31: Terror reigned in the York Street area. A band and ‘procession’ from across town attempted to invade Lancaster, Marine and St. George’s Streets-all Catholic areas.

June 12: Meeting of the Ulster Protestant League at Queen’s Square, at which fiery anti-Catholic speeches were delivered. After the meeting the usual procession took place to various parts of the city, and their route was marked by acts of gross hooliganism particularly window-smashing.

June 16: From 6 o’clock in the morning mobs were gathering, and there was heavy firing into Marine Street, Dock Street and other Catholic areas. Catholics proceeding to and from early Masses in St. Joseph’s were fired at by snipers. On this morning occurred the dastardly shooting of the 15 year old Annie Quinn on her way to Mass. For this crime a non-Catholic received three months hard labour. He swore to an alibi and produced witnesses to that effect, but later pleaded guilty.

June 17: This was the worst night of shooting since the beginning of the trouble. Volley after volley was fired into the Catholic quarter of North Queen Street, wounding one man in the stomach. As a result of urgent appeals from various sections of the citizens to put a stop to the growing anarchy, the Government at last decided to take action. On the following day the Minister for Home Affairs issued an Order prohibiting all processions, other than funerals, and the assembly of any groups or bodies of persons in any public place within the City of Belfast.

June 23: Sir Joseph Davison, addressing an Orange gathering at Hillsborough, referred to the above Order thus:

“You may be perfectly certain that, for the Twelfth of July Orange celebrations, we shall march through Northern Ireland. I do not acknowledge the right of any Government, Northern or Imperial, to impose conditions as to the celebration of the glorious anniversary of the victory of the Boyne, nor shall I acknowledge any authority to ban the celebrations which have been held almost continuously for 140 years. You may be perfectly certain that. on July 12th I shall be marching at the head of the Orangemen of Belfast.“

June 27: Four days after Sir Joseph Davison’s speech the Minister for Home Affairs gave way to Orange truculence and removed the ban on processions. It was clear who were the real rulers of Northern Ireland. Wild scenes-shootings, burnings, evictions, window-smashings, beatings-became the order of the day and the night. A strong appeal for peace by the Right Rev. Dr. MacNiece, Protestant Bishop of Belfast, had not the slightest effect.

July 12: Before describing the events of this and the following days, it is desirable to quote a passage from the Report made by Mr. Ronald Kidd for the National Council of Civil Liberties (London). This Council, of which he is the Secretary, sent Mr. Kidd to investigate the disturbances in Belfast. Arriving in time to witness those of June 12, he reports thus:

“At a riot on June 12 – at which I was present – following an inflammatory meeting of the Ulster Protestant League at the Customs House steps, an unruly mob of some thousands of men and women swept through the business quarter of the city. Men, not all of them sober, were dancing in the ranks and women were screaming as they marched. I pointed out to a constable that this was an illegal assembly at common law. The mob were getting out of hand; and. as they reached York Street, they ran completely amok A bomb was thrown into a shop; shots were fired; every window in the Labour Club was broken, and Catholic shop-windows along York Street were smashed in with stones and iron bolts One arrest was made, but the prisoner was rescued by the mob. We are justified in asking (a) why this dangerous mob, which was visibly out for riot, was allowed by the police to proceed on its way; (b) why nine armoured cars and hundreds of armed police were unable to effect even the one arrest which they attempted; (c) why this force of armed police were unable to prevent wholesale riot and damage.”

Another form of government apology is to say that the troubles were confined to one small section of Belfast and that the victims were Protestants, while the Catholics were the aggressors. it is true that the majority of the killed were Protestants; but there is no evidence whatever that they were killed by Catholics. Six of the seven were killed in the open when rioting was in full progress-none of them in his own home or in his own street. As to the seventh, there is good ground for believing that he was shot by non-Catholics for his sympathies with Catholics, with whom he was a great favourite in the district where he was shot. As to the Catholics, the facts are quite in contrast apart from those killed, there were twelve deliberate attempts to murder Catholics, and in five of these cases the victims were inside their own homes. That none of the twelve is dead is no credit to the assailants.

But the number of the murdered is no measure of the sufferings to which Catholics were subjected. There was no security of life or property. Day and night the Catholics were in terror of raids, shootings, burnings, evictions. Let us take this last item. In all 514 families, comprising 2,241 persons, were driven from their homes.

That account gives an idea of the background to events over the summer of 1935. However, it doesn’t make reference to the role of the IRA. Despite the overt threat of violent sectarian attacks, the IRA had continued with its annual summer camp at Giles Quay, just north of Dundalk. In 1932, the IRA had to recall units from the camp to provide defensive cover in districts that were under threat. In 1935, the IRA’s Army Executive recommended that the Belfast staff cancel the camp due to the potential for trouble in Belfast. In the end, the camp went ahead but an alert company from Ballymacarrett under Jack Brady remained ready to contain any problems. Jimmy Steele, as Adjutant, would be the senior member of Belfast Battalion staff present, while the Training Officer Charlie Leddy was to be the O/C for the camp itself.

At the camp the men stayed in six bell tents and two hiker tents pitched alongside a stream known as the Piedmont river. The camp wasn’t particularly discrete. The IRA didn’t take much in the way of precautions and did little to conceal their activities or to provide security such as sentries. By the time the men had cycled the sixty miles from Belfast, an advance party had the tents erected and a meal cooking on the camp fire. In the mornings at a training camp, participants usually formed up for parade and drill. The plan for Giles Quay, over the course of the camp, was to deliver lectures on various military matters with opportunities to handle, maintain and fire weapons. This included live ammunition from rifles and revolvers, the chance to fire bursts from a Thompson gun and throw Mills bombs.

On the Saturday at Giles Quay the volunteers had carried out drills, attended lectures and sat knowledge tests. Rifle practice took place using a sand dune as a target. That evening was declared a free night and some cycled off to Dundalk to find a ceili, while others visited people they knew in the locality. Jack McNally remembers that they were advised to be careful in Carlingford, which was considered a Blueshirt stronghold, to the extent that their accents shouldn’t be heard in the village.

Around the same time as the IRA men were leaving the Giles Quay camp for the evening, the Orangemen were on their return leg from the field back to their homes. There had been shots fired in the area on the previous night. Before the Orangemen reached York Street, they had clashed with residents in the Markets and Stewart Street, where shots had been fired. As the bands passed Lancaster Street on York Street a confrontation soon escalated into a major riot around Lancaster Street, Middle Patrick Street and Little Patrick Street.

Jack Brady had received a visit from a Mrs. Kelly of Seaforde Street (in Ballymacarret) and Sarah Trainor (from York Street) immediately after the trouble had broken out. They had came over to visit Brady and said there was shooting in Lancaster Street by the Orangemen on their way back from the Field. Mrs Kelly had told him it was desperate. Brady immediately rounded up thirty men with guns (IRA volunteers were already on duty and had been posted in pickets of 6 or 7). They went straight across the city and set up headquarters in Trainors Yard in Lancaster Street.

By the end of the day, the hospitals reported 17 people with gunshot wounds, 20 with other assorted wounds and two dead. The RUC had opened up with Lewis guns and snipers had been reported firing from roof-tops around York Street.

While most of the men were away from Giles Quay for the evening, word arrived from Belfast for Jimmy Steele saying that there had been a serious outbreak of violence and that it was mostly focussed on York Street. Steele wanted to take A Company, which covered York Street, back to Belfast along with any other units that wanted to leave. Those present discussed the situation until around 2 am, when Jack McNally returned from visiting a friend in Omeath. Since McNally was on the Army Executive and the most senior IRA man present, Jimmy Steele waited on McNally to get his opinion before a decision was made.

McNally checked on the reports from Belfast and pointed out to that, since they had no word of casualties (as yet), the men should go to bed and get up at 6 am, strike camp and head to Belfast. If they were stopped anywhere, they were to say there were a cycling club from the Markets on their way home. When the IRA volunteers woke in the morning they found large numbers of Garda, including the non-uniformed special police detachment set-up by De Valera and known as the Broy Harriers, walking up to 40 abreast in a wide sweep across the camp. The Broy Harriers detained a large number of the Belfast IRA volunteers and seized their weapons despite protests that both were needed immediately in Belfast.

When the IRA men were brought up in court in Dundalk to receive their detention notices they refused to answer their names. Many, like Harry White and Bobby Hicks, gave false names and addresses (a favourite being Craig Street – a tiny street with one occupied house).

When they were brought in front of the special court, Charlie Leddy made a statement from the dock:

“We deny the right of this assembly to try us as we are subject only to the jurisdiction of the Republic. The camp at Ravensdale had been there in three previous years. It was significant that in this year, when the war dogs and agents of British Imperialism were let loose in Belfast, that the bloodhounds were let loose against soldiers of the North coming into the area for training.”

They remained in action there for the rest of the 12th and 13th July, when Jimmy Steele managed to extract enough volunteers from various IRA units at Giles’ Quay and get back to Belfast. When he got there he told Brady:

You’ve done great work, but we’ll take over from here.

The riots, house-burnings and work-place evictions lasted for a further two weeks, leaving ten people dead, seven of whom were Protestants. Funerals, and funeral processions became the pretext for fresh outbreaks of violence over that period. By the 16th July, the violence spilled over the border as attacks and graffiti began appearing on Protestant-owned businesses in the south demanding they make public calls for attacks on northern Catholics to cease. While the attacks were largely uncoordinated, the Blueshirts appear to have been involved in a number of them (the IRA had no role in this campaign).

At the end of July all twelve arrested at Giles Quay were sentenced to two years in Arbour Hill at the Military Tribunal sitting in Collins Barracks. On their release, they found that their details had been passed on to the RUC. Any illusions the Belfast IRA might have still held about De Valera and Fianna Fáil had been quickly dispelled by their experience.

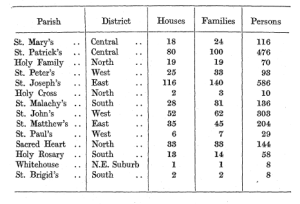

Within a couple of weeks of the Twelfth of July the level of violence dipped, but the memory of the 1935 Belfast pogrom (as it was regarded) was still fresh thirty-four years later in 1969, in Belfast (as indeed, were memories of 1920-22). This memory included the scale of the violence, and, around North Queen Street, even details such as the absence of the IRA at its outset. Another result was that the National Council for Civil Liberties began an investigation of what had happened. This was published in 1936 (I include a quote from it’s report here). Finally, some sense of the geography of the violence across Belfast in July 1935 is shown by a table included in ‘Northmans’ article.

Reblogged this on seachranaidhe1.

LikeLike