Commemorating the Easter Rising in the area under the control of the northern government was always a difficult matter for the IRA. In the early years after the Civil War, the main commemorative event in Belfast was actually, like Bodenstown, the existing Wolfe Tone Commemoration on Cavehill in late June or early July. In the 1920s, senior republican figures like Brian O’Higgins and Frank Ryan came to the city to gave the main oration. The Cavehill event often involved some form of cat-and-mouse with the RUC as republicans attempted to hold the event without any interference from the RUC, such as publicising the wrong time or place. In many ways this pre-figured the pattern that Easter Rising commemorations would fall into.

By 1926, and the tenth anniversary of the Easter Rising, comments at recent commemorations had prompted the northern government to ban any Easter commemoration at Milltown cemetery in Belfast that year, under the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (see here for a paper on bans under the Act). This was extended to include the Brandywell in Derry in 1927 and, by 1929, Armagh and Newry too (the list of places at which Easter commemorations were specifically banned continued to grow into the 1930s). In Belfast, the Easter commemoration became a set piece confrontation between republicans and the RUC. Since the wearing and sale of Easter Lilies was banned, as was the display of flags or posters, the presence of any of these would see the RUC attempting to arrest some of those present and there was often violence at the cemetery. Throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s, republicans were arrested at Easter for the sale or wearing of Easter Lilies (often derided in the court as Sinn Fein poppies) and erecting political posters.

One exception to the ban that was found, was the holding of religious ceremonies, so the solution that was often adopted by the Belfast IRA was to assemble at an undisclosed location then parade to the gates of Milltown (which were usually locked or guarded by the RUC). At the gates, the IRA and anyone else present would usually kneel down in the roadway and hold a short religious ceremony, usually a decade of the Rosary said in Irish by a senior IRA figure. The parade to the cemetery and the fact that the assembled volunteers were addressed by the Belfast battalion O/C or Adjutant (albeit in leading prayers) was taken to satisfy the requirements of a suitable 1916 commemoration. The paradox, of course, was that this way of circumventing the Special Powers Act ban also contributed to an impression that the Belfast IRA were primarily devout Catholics.

Most accounts of Easter Commemorations at this time appears as either RUC evidence in court proceedings or as police reports to the Minister of Home Affairs. Vincent McDowell, in his historical novel An Ulster Idyll, gives what may be closest to a republican account of a commemoration, in this case in 1941 (McDowell’s brother was an IRA volunteer and he himself was interned – and the novel was meant to be historically accurate):

It was resolved that the Commemoration in their Company area would take place on the Sunday afternoon just after the main Mass in St. Patrick’s when a crowd of people would be passing along and could be directed down a side street. They estimated that they would have possibly ten minutes… He met the others, at the corner of Frederick Street with North Queen Street, at the appointed time. The Company of volunteers took up position at various corners… A squad of volunteers diverted the people coming out from Mass by standing across their path at an angle and holding hands, calling out: “Commemoration, Easter Commemoration, just down Frederick Street, Easter Commemoration.” More than half the people walked down, mainly for curiosity… and as the small crowd began to gather of about one hundred and fifty people, Billy Kelly [the name McDowell uses for the local O.C. in 1941] stood on a table which had been volunteered by someone locally. The adjutant shouted: ” Attention! At ease!” Kelly started his brief oration.

“Friends, every year since the outbreak of the Rebellion in 1916, the Republican movement has always commemorated the birth of our Nation. Despite the enemy occupation of part of our country, we commemorate that birth here today. Easter is a story of the rebirth of the hope for all men, and particularly the Irish…”

McDowell then has Kelly read the 1916 Proclamation and three volunteers emerge with pistols and fire three shots into the air. He concludes…

A section of the crowd cheered and the others looked on, some with indifference, one or two with a certain amount of hostility.

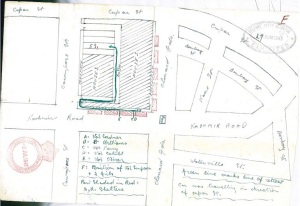

The planning for the 1942 Easter Commemorations saw the IRA deciding to stage a diversionary attack on the RUC in Kashmir Road. The planned operation was for C Company, under it’s O/C Tom Williams, to fire shots over an RUC cage car and draw the RUC into a substantial search of the area, forcing them to move men away from other districts. The C Company unit would retreat before the RUC saturated the area and the Belfast Battalion would hold its main commemoration without interference. The plan went wrong when the RUC pursued the IRA unit and there was an exchange of gunfire in Cawnpore Street during which Tom Williams was wounded and RUC Constable Patrick Murphy killed (apparently shot by William’s Adjutant, Joe Cahill). Williams subsequent claims of responsibility (as he had been led to believe his wounds were fatal) meant his was the only one of six death sentences that was not commuted. His execution was to add to the significance of Easter Rising commemorations for the Belfast IRA.

In 1943 then, the commemoration was to be particularly significant. It was held against the backdrop of a number of publicity coups for the IRA in Belfast. The leadership of Hugh McAteer and Jimmy Steele developed the idea of staging a public Easter Rising commemoration. Harry White (in his biography, Harry, written with Uinseann MacEoin) recounts how the idea evolved from a throwaway suggestion from two young IRA Volunteers to an operation involving sixteen Volunteers taking over the Broadway cinema to stage a commemoration. The wartime setting and heavy military presence resonated with Dublin in 1916. Similarly, the venue, built on the site of the Willow Bank huts from where the Belfast Volunteers had mobilised in 1916 provided a coded challenge to the various competing groups claiming primacy as the authentic inheritors of the Republic declared in 1916 (ownership of the Easter Rising commemorations were to see similar political battles in the 1950s when formal parades were permitted).

The 1943 commemoration also intentionally signalled a formal shift in the IRA’s centre from Dublin to Belfast, and in focusing on ending partition rather than challenging the legitimacy of Leinster House (the ambition of the Belfast IRA since the 1930s). While few enough may have understood the reference to 1916 and the pre-Treaty IRA (although those that did were the intended audience), the parallels of a public reading of the 1916 proclamation in 1943 in Belfast during a general world war and the original proclamation in Dublin in 1916 during an earlier war were no doubt clear. Symbolically, Easter 1943 marked the final shift in emphasis of the IRAs campaign to the north. McAteer, writing in 1951 in the Sunday Independent, clearly saw the parallels between 1916 and 1943.

Initially, according to White, the plan had been to simply flash up a slide on screen that said “Join The IRA”, but the concept expanded until it became a full dress commemoration. White had been staying at the house of a projectionist in the Broadway Cinema on the Falls Road, Willie Mohan, whose brother Jerry was an internée. Mohan’s uncle, Frank, was also the manager of the cinema. Typically, the projection box was kept locked, but normally the projectionist went for a smoke between films which gave the IRA a short window in which to go and take control of it. The RUC were expecting some form of commemoration to take place over the Easter weekend. According to the Irish News, they had turned the Falls Road into an armed camp with hundreds of uniformed and plain clothes police, with armoured cars, whippet cars, patrol cars and cage cars patrolling the district.

Despite this, on the afternoon of Easter Saturday, the IRA converged on a house close to the Broadway Cinema. They drew revolvers and grenades from the quartermaster and proceeded in pairs towards the cinema, walking within sight of each other for security. Armoured vehicles passed them but there were no incidents. Finally, the sixteen armed IRA men took up positions around the Broadway cinema on the Falls Road just before 5 pm. Some, armed with grenades, were on the flat roof to delay any potential raiders, the others took positions around the exits. Jimmy Steele and Hugh McAteer sat down in the audience and got ready to go out onto the stage. At 5.05 pm, as the film, Don Bosco, was ending the audience got to their feet and began to move towards the exits only to find that they were blocked by armed men. The armed men told them to go back to their seats and that no-one was going to be harmed. Meanwhile Steele and McAteer went up on stage.

“Are you the police?” asked one woman.

“No, it isn’t the police. It is the IRA and no-one is going to harm you,” was the reply.

Fr Kevin McMullan, who was 7 years old at the time and had just watched the afternoon matinee of Don Bosco recalls how excited the audience were as this happened. Since no advance notice of the event had been given, those present were simply the cinema goers who happened to be attending the film. Given that the film, Don Bosco, was a 1935 Italian film of the life of the Catholic saint, the IRA were assuming, at the very least, that the audience wouldn’t be hostile.

Three volunteers went into the projector box and handed over a slide which was flashed up on screen.

It said:

THIS CINEMA HAS BEEN COMMANDEERED BY THE IRISH REPUBLICAN ARMY FOR THE PURPOSE OF HOLDING AN EASTER COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE DEAD WHO DIED FOR IRELAND. THE PROCLAMATION OF THE REPUBLIC WILL BE READ BY COMMDT. GEN. STEELE AND THE STATEMENT FROM THE ARMY COUNCIL WILL BE READ BY LIEUT. GEN. McATEER.

Whatever the audience reaction was expected, Jimmy Steele, in full dress uniform, appeared on stage and was introduced by McAteer. Then, to a breathless hush, Steele read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic to the growing amazement of the audience. According to McAteer, “Through the stillness of the darkened cinema his voice rang clearly as he spoke the immortal words of the Proclamation.” It ended with a great burst of applause applause. Next McAteer read a statement from Army Council on IRA policy, the resonances with 1916 are clear. While the “cause had not yet triumphed” he told them, “Ireland is being held within the Empire by sheer force and by force alone can she free herself. Now with Britain engaged in a struggle for her very existence, we are presented with a glorious opportunity.” McAteer finished to applause and much enthusiasm. He then called for two minutes’ silence to commemorate those who had died for Ireland. Steele and McAteer then stood to attention (with McAteer wondering if their luck could hold). A voice then rang out “Volunteers, dismiss,” and Steele and McAteer jumped down from the platform and left the cinema. With proceedings over, the remaining IRA men left the building to much applause.

In Dublin, The Irish Times reported that no commemoration took place. In Belfast, though, The Irish News enthusiastically reported on proceedings which were recounted in news bulletins as far away as Germany. The northern government’s Prime Minister, J.M. Andrews, who was already under pressure as being perceived as a moderate, resigned on the Friday after Easter.

9 thoughts on “Early Easter Rising commemorations in Belfast”