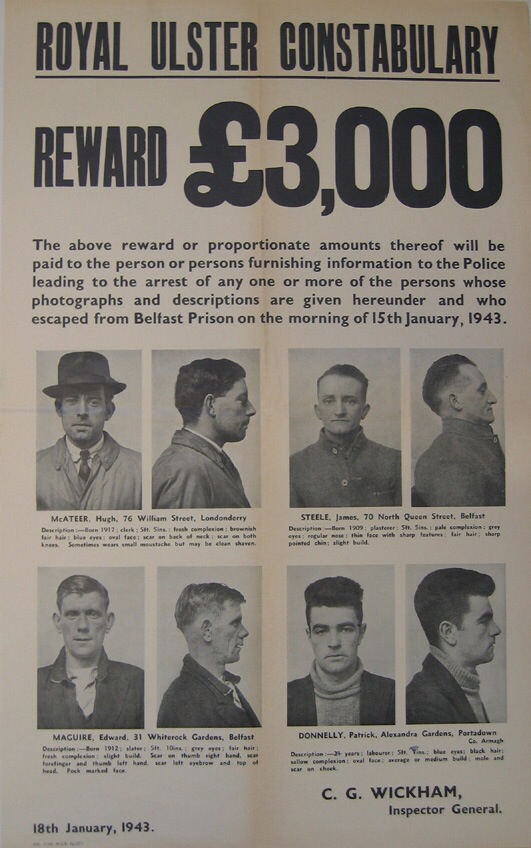

This is an account of events in A wing, Belfast Prison (Crumlin Road) on the morning of 15th January 1943 when Pat Donnelly, Ned Maguire, Hugh McAteer and Jimmy Steele escaped.

If you prefer a shorter version, you can see it here.

The day discipline staff arrived as usual at 7.30 am under Principal Officer William Nelson. Nelson didn’t normally perform this role, but on the 15th he happened to be replacing Principal Officer Graham who was on his day off. Nelson relieved the temporary Officer, Nicholson, who had been in charge of A wing during the night. Nicholson confirmed that 115 prisoners were present in A wing and completed the hand over. Two warders went on duty on A1 (James Johnston and Joseph Carson), two on A2 (George Tate and Charles Hipson) and one on A3 (Robert Haddick), which housed only twenty prisoners. The warders moved to their stations on the various landings.

Prison Officer James Johnston confirmed that 43 prisoners were present on A1. Johnston was 40 years old and had been a prisoner warder for four years having previously completed 15 years service in the Royal Ulster Rifles where he had risen to the rank of Sergeant. He lived in Roseleigh Street. He opened the cells so that Ned Maguire (brother of the Belfast IRA O/C) and the orderlies could begin first slops and the usual morning routine. On A1, the other orderlies were Frank McKearney, James Kane and Anthony McMenemy.

Prison Officer George Tate and Charles Hipson, a native of The Curragh in County Kildare, confirmed that 52 prisoners were present on A2 when they relieved Nicholson. They opened the cell doors to allow the orderlies, Joe McKenna, George Crone, Arthur Kearney, David Barr, Vallely, McCoy and Michael Walsh, to begin their rounds. Barr was the only orderly on A2 who wasn’t a republican prisoner. Hipson began to go around the cells, opening the doors for slops, while Tate followed in his wake. When Pat Donnelly’s cell door was opened, he made a request to Tate to see the doctor, saying he had diarrhoea (Donnelly was O/C of the IRA unit in A wing). When interviewed that evening by Sergeant Maguire of the RUC, Hipson admitted that, to make it easier for second slops, doors regularly had their bolts drawn across rather than having the key turned in the lock.

Temporary Officer Robert Haddick, a former B Special, confirmed that 20 prisoners were present on A3. He open the cells of the two orderlies, Stevenson and Edward Dalzell, and they began first slops. Haddick also opened the lavatory on A3.

The handover had occurred at 7.30 am. Nelson then left to open the passage gate and workshops, entering the A wing yard. Nelson hadn’t noticed anything unusual.

The day and time had now arrived. The warders began to distribute tea, bread and milk for breakfast on A1 just before 8 am. None of the escape team managed to eat their breakfast apart from Jimmy Steele who drank his tea. Having drank his tea, Steele asked permission to go to the lavatory from James Johnston. His cell door was left unlocked awaiting his return. Steele began the escape attempt by walking up the staircase of A wing in full of view the warders on A1, A2 and A3. Ned Maguire simply followed him up the stairs. According to Billy McKee, despite the regulations, prisoners regularly might move between wards (as the floors were known) to return a book or for some other errand even though it was expressly forbidden. It was hoped that a member of prison staff who noticed movement on the stairs would assume that that was why Steele and Maguire were on the stairs.

On A2, Pat Donnelly had asked permission from Tate to visit the toilet due to his diarrhea. Donnelly was now just ahead of Steele and Maguire on the stairs. On the way up the stairs to A3, Donnelly saw McAteer’s cell being left unlocked after he too had requested permission to visit the toilet. As McAteer emerged he saw Steele and Maguire following Donnelly up the stairs. The whole escape team had now arrived on A3, in plain sight of any of the warders who might chance to look up to the Threes landing. The staff were mainly concentrating on opening cells and distributing breakfast.

The escape team covered their boots in prison socks to deaden the sound of their footsteps on the landings. While Haddick was distributing the breakfast and wasn’t watching the lavatory they entered and organised the tables so they could open the lock then climb up through the trapdoor and into the roof space. It was already arranged for the tables to be moved away from the trapdoor after the escape. To save time, the lock had been picked the day before and plugged with soap so it appeared closed.

Meanwhile, the orderlies, who were nearly all republican prisoners, had been detailed to close the cell doors of the escape team to delay discovery as long as possible. Some prisoners even staged one way conversations with some of the escape team, hovering at their cell doors to maintain the pretence that they were still inside. So far, nothing had raised the suspicion of the warders. Indeed, George Tate, on A2 was convinced he had saw Donnelly return to his cell and locked the cell when he gave a statement on the escape that afternoon.

The escape team had now all assembled in place in the roof-space. They walked down the roof space, over the occupied cells on A3 and as far as the Circle, from where they turned back and stopped at the point where the roof had been weakened. They collected the escape equipment such as the ropes and rope ladders that had been hidden in the roof. They lit a candle to allow them to find the place where the roof timbers and slating laths had been sawn through and they intended to break their way through the roof. Ned Maguire tried to force the slates free but pushing them up was more difficult than expected. A spare pair of trousers later found in the roofspace below the hole may have been used to dampen blows on the slates. As the seconds ticked by, trying to lever the slates up was abandoned in favour of brute force. Finally, the would-be escapers held their breath as the first slate parted from its nail. The sound, in the confines of the roof space, echoed like a gun shot. Everyone tensed as they waited to hear where the first whistles blow to signal their discovery.

For the first few seconds there was silence. Then another few seconds. The, slowly, everyone began to breathe again. Examining the hole made by the first slate, they carefully removed enough that they might get themselves up through the opening and onto the roof. Still, there wasn’t yet any sound or hint of movement in A wing or outside. The 30 foot rope was secured to a roof beam by Ned Maguire and slipped out and over the end of the eaves dangling into the darkness in the yard below.

Maguire was the first man to climb up through the opening in the roof. As he exited through the slates, far off to his left he would have seen the outline of the armed warder who guarded the main gate. He began his descent. All the way down he awaited the tell-tale sounds of warders assembling to intercept him at the bottom of the rope.

On reaching the ground Maguire discovered he was alone. As Steele climbed out, he edged down to the eaves then, grasping the rope, headed down to the ground. Shortly Maguire was joined by both Steele and Pat Donnelly. McAteer was deliberately positioned as the last man to descend the rope ladder. Having previously had a big fear of heights, there was a significant risk that he could freeze on the roof or rope and trap anyone behind him until he was able to either move back or forwards. Chances were that he could lose his nerve completely and effectively stop anyone following him.

Even as a former Chief of Staff, McAteer was not afforded any indulgence by the rest of the escape team. Once Steele, Maguire and Donnelly had all reached the ground they continued with the escape plan without waiting for him. The arrival of the escape team into the prison yard had not gone unnoticed, though. Once on the ground and moving across the yard, they were observed from the ground floor of A wing. The person they had been spotted by, though, was the resident of a cell on A1. However, their arrival had been expected since the shaft that had been manufactured for the hook was assembled in that cell in A1 and was now passed out through the window.

Meanwhile, Hugh McAteer had surprised himself as, pumped with adrenaline, he had climbed through hole in the roof. Over to his left he could still see the armed guard standing inside the front gate. Directly below him he could make out Steele, Pat Donnelly and Ned Maguire, having collected the shaft from the cell window and now en route to the outside wall. McAteer gripped the rope, swung himself over the eaves and quickly descended the thirty feet to the ground. He then moved across the yard to join the rest of the team at the wall.

McAteer reached the wall as the rod was being attached to the hook. Once it had been secured, they tried to attach the hook to the top of the wall. Even though the hook was smothered in bandages to try and catch the barbed wire, it stubbornly refused to take a grip as it was several feet short. To make good the shortage, Ned Maguire climbed up on McAteers back and tried to put the hook into position. The toe of Maguire’s boot, digging into McAteers back, caused McAteer to squirm and lose his balance. The hook, shaft and ropes being carried by Maguire, crashed, along with Maguire, to the ground. Again the sound seemed to echo loudly across the prison yard.

Maguire turned on McAteer: “Why the hell did you have to start wriggling just then?”

But McAteer snapped back: “God Almighty! Do you think I did it for a joke?”

At that point, Pat Donnelly cut the argument short: “I think, lads, that you should finish that discussion on the other side of the wall.”

McAteer then tensed himself and Maguire swarmed up the former Chief of Staff’s back and tried to stretch and use the rod to hook the rope-ladder into position. The account of the escape published in the Republican News claimed that, after a couple of unsuccessful attempts, they only succeeded in putting the rope-ladder when a third man climbed up on the first two and finally succeeded. Given his size, if the Republican News version is correct, then this third man must have been Jimmy Steele.

However, it was hooked into position, the first up the rope-ladder was Ned Maguire and he placed a blanket, folded in four, over the barbed wire to give some protection to their hands. Once that was done, Ned Maguire slipped over the barbed wire, grasped the down-rope placed on that side then began to descend the other face of the wall. With that, he disappeared from the view of the rest of the escape team.

Jimmy Steele and Pat Donnelly followed Maguire, keeping to the same pattern as had held on the roof with McAteer filling the final place to minimise the risk of his fear of heights jeopardising the others’ chances. Steele climbed the rope ladder, passed over the blanket then, holding the down rope, continued to the ground on the other side of the twenty-odd foot wall. After twenty-five months of being confined inside the walls of the Belfast Prison on Crumlin Road, he was now found himself staring at the outside of perimeter wall of the jail. When he reached the bottom he turned around to see that he was alone in the entry that ran along the back of the warders cottages.

As had been agreed at the outset, Maguire hadn’t waited for Steele to appear. Neither was Steele to wait on Donnelly. Each man over the wall was to walk away. That had been the plan. As GHQ, the Northern Command or the Belfast hadn’t been forewarned, there wasn’t a waiting car to whisk them away to safety. So every second counted. Each hurried down the entry and out onto the Crumlin Road and headed towards Trainors Yard in Lancaster Street, the one arrangement that the escape team had put in place. Out on the Crumlin Road, a warder passed Jimmy Steele on his way in to his shift in the prison. The warder acknowledged Steele, then continued without reacting, towards the prison gate. He never reported seeing the escapers.

In real time, Jimmy Steele, Ned Maguire and Pat Donnelly had all emerged from the entry within seconds of each other. As the escaper with the most intimate knowledge of that part of Belfast, Steele headed off intending to take the shortest route possible. The others had also memorised the route but might have to pause to keep their bearings. They ran straight across to Florence Place, alongside the Belfast Court House and headed towards the Old Lodge Road. Despite the fact that he, Maguire and Donnelly were all wearing prison clothing, they managed to pass, more or less unnoticed, through the early morning crowds around the wartime Crumlin Road and the adjoining districts. Walking within sight of each other they arrived in Lancaster Street.

It was now 8.30 am. The escape, including breaking through the roof, assembling the hook and pole and making two attempts to catch it on the top of the wall, had taken roughly fifteen minutes. When the authorities, as part of their investigation, had an officer go over the escape route in daylight, with the roof breached and all the escape equipment in place, he also did it in fifteen minutes. The second team (John Graham, David Fleming and Joe Cahill), scheduled to make their attempt at 9 am and anyone who followed them, would still have the cover of darkness if they did it in the same time (Graham had reputedly told Billy McKee and others to take their chances once the second team had gone).

However, Hugh McAteer, the last man in the first escape team, hadn’t yet got over the wall. He began to climb up the rope ladder, but, having held the ladder out for the others, found that the effort had put too much strain on his arms and, quite likely, that the adrenalin of the roof top descent had also worn off. Suddenly, his arms could no longer pull his weight up the rope ladder and, eighteen foot up the wall and, only a couple of feet from freedom, he had to let go. McAteer dropped back into the prison grounds. He landed awkwardly on his left ankle and collapsed onto his back, having the breath knocked out of him. After a moment’s pause, though, McAteer got up and raced up the ladder.

At the top, he discovered that, to manoeuvre himself over the top of the wall and reach the rope to descend the other side, he would need to rely on his weaker left arm to safely complete the task. Since he felt he couldn’t trust that his left would support him on the blanket covering the barbed wire, he momentarily grasped the exposed barbed wire with his right hand instead. He paused for a few seconds to get his breath again. However, he then felt a surge of pain from the barbed wire sticking into his right palm. Instinctively withdrawing his right hand, his left was unable to reach the down rope to make a controlled descent down the wall via the rope. Instead, he fell the twenty feet to the ground again. This time, at least, he was on the outside of the wall, looking at the rear of the warders’ cottages.

As well as his ankle, injured falling back into the prison, he now had a pain in his knee. Once he got to his feet he noticed that his right hand had left a bloody print on the ground. Realising that no-one else had waited for him, McAteer later wrote that he felt a fleeting sense of satisfaction in the knowledge that discipline had triumphed over the ordinary human instinct of comradeship. Thrusting his bleeding hand into his trouser pocket he hobbled past the back of the warders cottages and out onto the Crumlin Road. Later, McAteer thought his attempt on the wall had taken him only two minutes but it had actually taken five. It was now 8.35am.

But McAteer had also been seen. A boy on his way to school had observed McAteer coming out of the prison. It just so happened that the same boy, Lancelot Thompson, was the son of the warder of the same name who lived in one of the cottages McAteer had just passed. He rushed in to tell his father.

Meanwhile, back in A wing, the day discipline staff were finishing the morning round and preparing to do a count before heading off for their breakfast at 8.30am. The night guard had signed over 115 prisoners to them that morning. Ten minutes before McAteer had headed over the wall, at 8.25am, the day discipline staff reported the number of prisoners in the normal fashion. Once they collected the numbers from A1, A2 and A3, they established that the number of prisoners they had locked back into their cells was still 115. A few minutes later they went off for their breakfast.

Cahill, Graham and Fleming, confined to their cells until 9am, strained to hear of any sound that might indicate that the first team had failed or their asbsence had been discovered. At 8.30 am, on the wing, all appeared normal.

At the same time, Hugh McAteer, despite struggling with the pain in his leg and bleeding profusely from his hand, attempted to follow Steele and the others to the pre-arranged safe house. Lancelot Thompson junior, by now, had rushed back to his father, Lancelot Thompson, who had just come off the night guard and was preparing to go to bed. Thompson, having been told what his son had seen, rushed out to go to the prison gate and raise the alarm. With his laces untied and his coat unbuttoned, his father rushed up to the prison warder at the front gate and raised the alarm. He also noted the time. It was now just after 8.35am.

Out on the Crumlin Road, the vagaries of wartime clothes rationing meant that few people took a first, never mind second, glance at the escapers. McAteer had attempted a short cut, but lacking sufficient knowledge of the streets around the Crumlin Road, had to retrace his steps to find a recognisable landmark. Once he did and managed to find Carlisle Circus, he was just in time to witness warders racing past on bicycles searching for the escaped prisoners. He even passed other warders who were clearly on their in to the prison to begin a shift.

Riordan, a prison officer originally from Cork, ran into A wing shouting “Lock the up. Lock them up.” The prisoners were still locked into their cells. The second team and those that intended to follow them realised the opportunity had gone.

Some fifteen minutes later, on the verge of collapse, McAteer finally arrived at the address Steele had given as the safe house, only to discover the others had safely arrived. It was now almost 9am. Steele, Maguire and Donnelly practically had to carry McAteer upstairs to bed. When they prepared to examine his injured leg, Pat Donnelly pointed at his feet. McAteer still had his prison socks covering his boots. As McAteer later wrote:

“We all stared for a moment in surprised silence and then for the first time that morning we laughed. With that, the tension lifted and I felt, with a tremendous surge of exultation, that I was free again, really free, after less than two months.”

You read some more about the escape here.

pure determination and a lot of faith probaly would have been shot on sight they certainly kept the faith

LikeLike

I didn’t mention it but the RUC patrolled the outside armed with sten guns. As it happened, when they went over the wall they could have ran into the patrol in the entry behind the warders cottages. The RUC man was in Landscape Terrace (the street just past the Crum) having a smoke and didn’t see them. Because it’s all tidied up now you can see up along the wall behind the cottages where they went over. Whole thing could have fallen apart at any stage. If they’d met an RUC sten gun, there’s no doubt one or two may have been killed on the spot.

LikeLike